When I initially introduced myself to this course and its material, I had strong reservations about my place researching the life of a fourteenth century individual. While my academic background is varied and I have taken a few history classes set in the Medieval period, it was about eight years ago. My more recent work has been focused on the sacred landscapes of the Bronze Age in Greece and on digital applications in archaeology. At first glance, there are no obvious connections between Roger de Breynton and his world of Herefordshire, England and my current fields. Context is so crucial to archaeology that I found it difficult to conceive of a project, of doing work without the context of the world that Roger was living in. Luckily, over the weeks of applying the digital methods I am familiar with and learning new ones, I was able to come to the realization that landscapes are fundamentally the same. Sure, there are differences in soil, vegetation, topography and all sorts of other things, but understanding how people interact with the land is some kind of a universal truth.

Armed with this understanding, I envisioned a project that would combine my interest in Geographic Information Systems (GIS) with the world of Roger de Breynton. It started thus:

No. 196 1316, April 3.

Charles and Emanuel, A Calendar of the Earlier Hereford Cathedral Muniments 1955, 764.

1. Roger de Luyde;

2. John le Gurdlere and Alice, his wife.

GRANT of a messuage lying in the street of Wydemarsh’ in the suburb of Hereford between the land of grantor and the land of dominus Hugh the wheel-wright (rotar’), chaplain, and extending in length from the high street as far as the water called Smalpors and containing in width in front five ells and one quarter with inches interposed and as many behind in width. Given at Hereford.

Witnesses: Gilbert le Gamit’ (Gaunt’?), bailiff of the fee of the hospital, John Steuenes, Henry the dyer, Richard de la Lastres, John de Dudeleye, Robert Sauage. Latin. Seal.

Contained in this document from the Hereford Cathedral Muniments (HCM) is an incredible amount of useful information. For starters, there are nine individuals listed. A few of them have family connections – John and Alice, spouses – while others have professions – Hugh the wheel-wright, Henry the dyer – and still others have civic or religious positions – Hugh is also a chaplain, Gilbert a bailiff.

Beyond the people listed in HCM 196, the language referring to the land itself is at once intriguing and opaque. For someone not well versed in medieval history, a long series of questions arises. Some are more answerable than others. For example, what is a messuage? A cursory internet search will take you to a number of dictionaries which define the term as a house with its surrounding lands and additional structures – orchards, gardens, barns, and the like.1 Unfortunately not included in any definition is a generic size – a messuage could vary in scale.2

If the plot of land itself can vary in size, what then about the measurements included in the document? “In width five ells and one quarter with inches interposed and as many behind in width” is somewhat of a word salad. Fortunately, a dictionary is once again a useful tool. An ell was a unit of measurement of about 45 inches or 1.14 meters.3 That puts our messuage at about 236 and a quarter inches or 19.7 feet or about 6 meters wide. This width does not seem like enough for a house, let alone a house with additional buildings and arable land, but perhaps the need for a house or dwelling on a messuage was not strictly necessary. At any rate, there was a small plot of land intended for some sort of use at Hereford in the street of Wydemarsh’ in April of 1316.

The placement of this plot of land is the key point of the document. HCM 196 represents a common trope in the land grant documents of the Muniments. In 1316 when the grant took place, land was defined by its boundaries. Arable plots were segments of large fields, some enclosed and some not, that were farmed by the owners or rented out in pieces to individuals willing to farm them. Widespread enclosure of the land with low field stone walls did not occur until about four hundred years after HCM 196 was written, in the mid 1700s.4 Because one open field might have several tenants or owners, boundaries for grants of land are defined by those neighbors.

This is the kind of bounding we see in HCM 196. The messuage in question is located and bounded by “the land of grantor” – likely Roger de Luyde – and “the land of dominus Hugh the wheel-wright”. Indeed, many documents supply held lands for all four boundaries, such as in HCM 1751 which lists one of its granted acres as lying “in the field called Estenoveresfeld between the grantor’s land and that of the rector of the church of Estenovere and extend[ing] from the grantor’s land to that of John de Underdoune.”5 HCM 196, then, is one of a batch of documents that is unusual in that two of its boundaries are not lands held by other people.

The length of the messuage in HCM 196 runs “from the high street as far as the water called Smalpors” and 6 meters in width for that entire length, presumably. We might imagine something akin to the figure here, where the orange represents our discussed messuage, bounded on either side by the green and blue lands of Roger de Luyde, grantor, and Hugh the wheel-wright, and has it’s long termini at the high street on one end and the mysterious Smalpors at the other. But being able to visualize the land described in the documents in colored boxes is not an entirely useful way of understanding and discussing the landscape of Hereford during Roger de Breynton’s lifetime.

The scope of this project, then, picks up on this thread of useful exploration, understanding, and visualization of the Medieval landscape. The HCM provides a wealth of information about how the land was used and exchanged during Roger’s lifetime. In order to understand his place in his world and, further, to understand his journey from the small village of Breynton to a more global stage, we must first understand where we came from. To that end, this project seeks to identify the plots of land discussed in the HCM on the natural landscape of Herefordshire. The following sections discuss the methodologies behind document selection, segmentation, and the place-name research process, preliminary findings, and the wider implications of this project in regards to Atlas of a Medieval Life (AML).

Methods

This study was conducted with fellow project member Jack Rouse. While we had different project ideas and outcomes, the data collection and processing was done as a team over a period of several weeks. As such, the following methodology sections relate the work done by both of us to select and segment the documents and to subsequently begin the process of land identification.

Document Selection

Selection of documents was limited to the aforementioned HCM because of the kind of document required for this study. Additional sources for contemporary documents do exist but do not commonly discuss grants or leases of lands. The HCM itself contains over five hundred documents, two hundred and fifteen of which were previously processed and corrected for the AML project. Of those two hundred and fifteen documents, twenty-seven were found to fit the criteria of the project, namely that they either had a specific placement, such as “a curtilage lying in Brutone strete in the suburb of Hereford” in HCM 174, or were bounded by natural or named features on at least two sides, as seen in HCM 196 above. The majority of the documents in fact had both of these features.

Document Segmentation

Following the identification of those twenty seven relevant documents, we began the process of breaking each down into its most pertinent parts. For our purposes, these were the number and date of the document, the various locations included, and the parties involved. For explanatory purposes, this is the initial entry for HCM 196:

| document_identifier | year | town | secondary_location | transaction_type | land_type | party_one | party_two | border_one | type | border_two | type | border_three | type | border_four | type |

| HCM 196 | 1316 | the suburb of Hereford | the street of Wydemarsh’ | grant | a messuage | Roger de Luyde | John le Gurdlere and Alice, his wife | the land of grantor | property | the land of dominus Hugh the wheel-wright, chaplain | property | the high street | road | the water colled Smalpors | natural feature |

Basic information such as the document identifier were included for ease of identification. Year was used to sort the documents chronologically. Transaction and land types were collected for statistical purposes and to examine commonalities in the exchange of land. The parties involved in each transaction were recorded to explore whether specific plots of land seemed to be changing hands more frequently or if particular individuals were renting or leasing land more often. Locational data was collected for the stated aim of the study, to identify these plots of land where possible. Borders were typologized generally based on the categories of “property” for owned lands discussed as “the land of” an individual or collective entity, “road” for any street or highway names, “building” for any named structures, and “natural feature” for elements of the landscape such as waterways and fields.

Place-Name Research

After completing the segmentation of the twenty-seven studied documents, we began work on attempting to locate the places mentioned within them. The first step of this was to identify the modern names of each place discussed. We did this by working systematically through the segmented documents, establishing first the modern names of the towns, then of any secondary locations mentioned in the document, and finally of the borders of the transacted land.

For the most part, town names changed very little, typically only with minute vowel shifts, such as from Medieval Werham to modern Warham and Fowehope to Fownhope. Larger municipalities, such as Hereford itself and Ledbury, remained largely unchanged in their designations. These parishes were identified typically with simple internet searches and guidance from the AML project director, Dan Birkholz. For example, his knowledge that Breynton was in the Medieval period made up of several small parishes, including Werham, allowed us to easily locate modern Warham near modern Breinton and not confuse it with similarly named parishes in other shires of England.

Secondary locations proved a harder challenge as these are on the whole street or field names, such as “the street called Wronhthale” in HCM 1752. For the streets of Hereford, we were able to find a map (left) of the Medieval city’s streets which was instrumental in identifying the roads mentioned in the documents.6 The map allowed us to identify every street mentioned as being located in Hereford with the exception of “the highway”, which is less identifiable. The Medieval streets correspond accurately with the modern street locations. Additionally, streets from parishes other than Hereford remained quite elusive as there does not seem to be a parallel map for the shire at large or its other populous towns. These other streets, as well as borders, classified as “natural features” were often pinpointed based on best guesses. Modern names were determined based on Arthur Bannister’s 1916 The Place-Names of Herefordshire, which helpfully collects the modern names of a wide variety of locations and includes early and divergent spellings of those locations. For example, the entry for modern Fownhope lists in chronological order by source the alternatives “Hope” from 1086, “Fanne Hope” in 1243, “Fawehope” in 1269, “Fonhope” in 1278, and finally “Fowehope” in 1291 as it appears in HCM 593.7 The volume also offers a variety of naming conventions that made unlisted locations such as “Parva Brompton’” identifiable as Little Brampton and “the field called Estenovesfeld” as Eastnor Field.

Identification of Document Locations

Once determinations were confirmed and probable names were completed, we turned to the identification of the actual locations. This often occurred alongside the identification of the modern name of the location. Tools used include: Google Maps, Ordnance Survey (OS) maps, as well as a variety of older maps dating from the sixteenth to nineteenth centuries.8 Rather than a wholly scientific approach to this portion of the project, I often found myself starting from a parish such as Warham or Ledbury and exploring the surrounding environs on the OS maps to get acquainted with the terrain and features. This often led to identifying probable locations accidentally and allowed me to get a grasp on that all-important concept of context that I felt I had been missing. Using the OS maps in particular allowed us to pinpoint specific locations via an “OS number”, which is a coordinate system specific to the OS maps, as well as a more traditional longitude and latitude.

Preliminary Findings

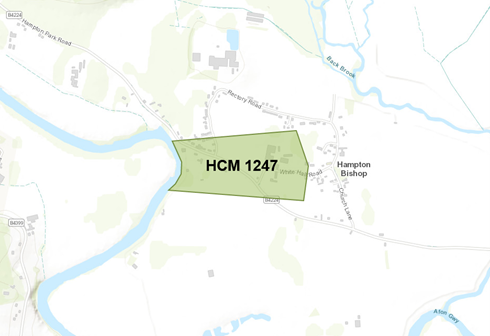

The stated goal of this project was to place the plots of land discussed in the HCM documents into the physical space of modern Herefordshire in order to understand the relationship between the natural landscape of Herefordshire and the people who inhabited it. Due to the scope of the research necessary to definitively place all of these mentioned locations, the work is not nearly done. Instead, we have made important headway into the topic. Of the twenty seven documents we worked with for the project, fifteen have yielded solid preliminary data.9 For the purposes of this paper, I will discuss four: HCM 174, 196, and 608 in Hereford and HCM 1247 in Hampton Bishop.

Owing to the guesswork involved in identifying some of the modern names and the limitation of having only two borders that are not designated based on ownership, our ability to plot land was quite restricted. Nevertheless, in the maps below are the probable locations of four such plots mentioned in the HCM.10 The first image identifies two rather small regions for the likely locations of the lands mentioned in HCM 196 and 174 as well as the large range of possibility for the land in HCM 608. These were all triangulated with two known borders.

HCM 196, with its location on modern Widemarsh Street and its terminus at the modern High Street, does not cover a large area of land, which corresponds to the six meter width mentioned in1 the document. Likewise, the land in HCM 174 between the modern Mill Street and Green Street has a small area. HCM 608, with its placement in “a field called La Reye”, offered a challenge. Bannister’s Place-Names suggests a connection between The Ryelands and “le Rye” or “tres Ryes” and a placement near Hereford.11 The document states this field to be in modern Warham which complicates things despite Warham’s location due west of the assigned map block. However, other options listed in Place-Names that might coincide with “La Reye” – “The Rea” and “Rea Farm” – are in Bromyard and Ledbury respectively, a fair distance from Warham and Hereford.12 Thus, this location at the Ryelands seems to be the strongest hypothesis at this point in the research.

The only highly identifiable location outside of Hereford as of now is located at Hampton Bishop and is shaky at best. HCM 1247 mentions “a parcel of pasture” in “the field called Colcham” in Homptone, modern Hampton Bishop. Based on searching the surrounding region and researching possible name evolutions from Colcham, the best guess for this location is the eastern edge of the below map block, which seems to be in a space referred to today as “Colcombe”. The other identifiable terminus in this document is the River Wye, located at the western edge of the map block. This is a rather large swathe of land bisected by modern roads that are likely built over those of the Medieval period, but narrowing this area further is impossible, at present.

Wider Implications and Future Goals

The lofty ambition of this project was rather apparent to me immediately upon starting it, but the excitement I felt reading through HCM 196 for the first time has not abated through the research process. If anything, I am more energized than I was at the outset to continue the project. With much of the groundwork completed, a longer ongoing project researching naming and land-use in the fourteenth century would likely be able to better and more widely pinpoint the land in the documents. Once that necessary step is completed, I believe and hope that we will be able to better understand the relationship between the topography of Medieval Herefordshire and its people, Roger de Breynton included.

Appendices

Appendix I: HCM Land List

Appendix II: Research Tools for Land Identification

Notes

- “Messuage” at Merriam-Webster; “Messuage”. ⤶

- It is not uncommon for documents to list the specific acreage of the land being transacted, though acreage amounts do not coincide with the term “messuage”. ⤶

- “Ell” at Merriam-Webster. ⤶

- “Enclosing the Land”. ⤶

- Charles and Emanuel 1955, 690-91. ⤶

- Lovell Johns’ Medieval Streetnames. ⤶

- Bannister 1916, 76. ⤶

- Mapping resources are detailed in Appendix II: Research Tools. ⤶

- The full spreadsheet of the researched HCM documents is in Appendix I: HCM Document List. ⤶

- Maps were generated using ArcGIS. ⤶

- Bannister 1916, 167. ⤶

- Bannister 1916, 160. ⤶