John Iweyn was a steward, sheriff, and landholder who was active in and around Hereford until his death on May 28, 1321. He stewarded lands in Gower, Wales under William de Breose, the acting lord, and was also deputized by Hugh Despenser the Younger on behalf of King Edward II. Iweyn built and ran a corn mill on the land he held and bound the people who lived there to use it.[1]

The Landscape of Iweyn and the Despenser Rebellion

During the years 1318-1321, tensions were high as Despenser worked to hold as much power as possible. Seymour Phillips says, “By December 1320 the ambitions of Hugh Despenser the Younger in the Welsh March had won him a great deal of valuable territory but with it the enmity of some of the most powerful of the marcher lords, the earl of Hereford… as well as Hugh Audley and Roger Damory,”[2]. Despite the enmity, Despenser had the king’s favor and thus could not at this point be deposed. Instead, he was often blocked on his quests of ambition by the nobles who hated him, especially in his efforts to gain the inheritance of the lands and lordship of Gower. When de Breose allowed bidding for lordship over these lands, it appeared as if Despenser would win. To prevent this, de Breose instead privately passed the lordship to his son-in-law John de Moubray. This would prove to be a bad move as King Edward II accused de Breose of passing down the lordship without the king’s explicit permission and the lands of Gower were seized again by the king—and therefore, Despenser had access to it. In the early months of 1321, Iweyn sent word that attacks on the land were coming, and in the fighting that ensued, John de Moubray chased Iweyn to Swansea, accused him of conspiring with Despenser, and summarily executed him. This of course led to accusations of treason and de Moubray’s own execution, but the damage was done.

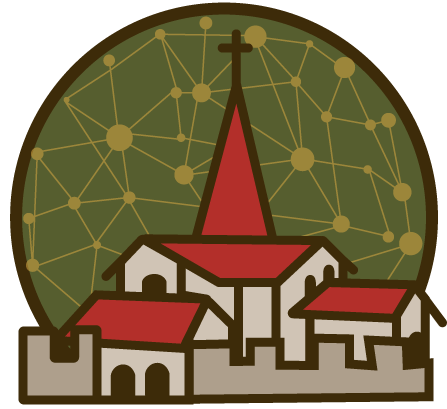

Thus, one might call Iweyn a pawn in a larger game. The visualization labeled ‘Figure 1’ shows us marked allies and enemies of Iweyn in his time as steward of Gower and sheriff of Glamorgan, many of which held the land of Gower at one point or another. What is interesting about this figure is that according to documents William de Breose granted Iweyn a lot of land and license, and so they would appear to be friends if not allies. However, de Breose also enabled his son-in-law de Moubray to seize Iweyn’s land after his death and plotted against Despenser’s takeover. Therefore, William de Breose is marked as a different color node than the others due to the finicky nature of his history with Iweyn. The limitations of documents to Hereford legal documents mean that certain documents are left out of the official dataset. In Figure 1, some nodes are marked with different-colored edges to others; this means that we know these connections exist, but they are not within the Hereford Cathedral Muniments. Business done with Hugh Despenser, for instance, was apparently not done in Hereford. An Iweyn-centric network might show us a web of Gower-based connections and explain in more depth where some of these allies and enemies fit. When scanning the Hereford documents, many of the existing Hereford connections for Iweyn come up in the early 1320s, when Edward II was tying up all the loose ends from the rebellion against Despenser and his own rule. This is where we find Isabella de Burgo, for instance, in a writ issued July 10 1323: “WRIT of Edward II directed to Isabella de Burgo, lady of Gower. The writ recites that an inquiry conducted by Richard Wroth, formerly guardian of the land of Gower, established that John Iweyn at his death was seized of the castle and vill of Locharn…The king therefore directs the said Isabella to restore possession of the said lands and tenements with their profits to (William Rokulf).”[3]

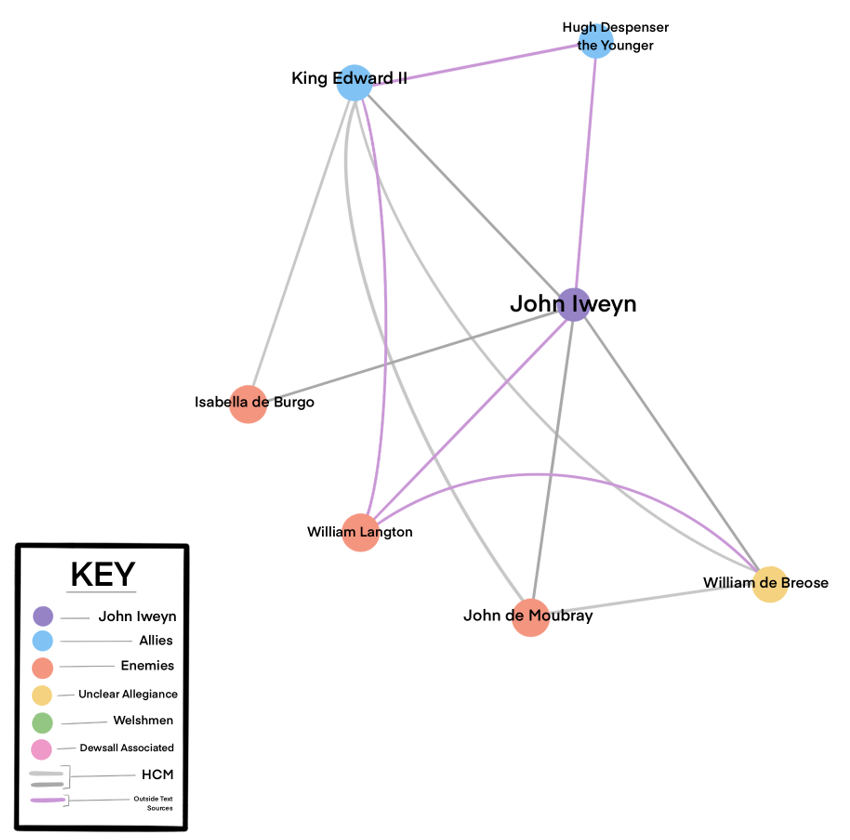

What about those who don’t hold land, but are instead beholden to it? Figure 2 shows Iweyn’s connections to local Welshmen via the muniment documents. These Welshmen are mainly found in Hereford documents 1523 and 1768, which have to do with Iweyn’s water mill and grants or bonds involved in its construction. Document 1523 states, “BOND of Lewelin ap Oweyn, Willyn ap Oweyn, Gruffith ap Oweyn, Cradok ap Morgan, and Morgan ap Cradok to John Iweyn. When the said John or his assigns shall have made a mill…the persons here bound…will do suit of mill there. Furthermore, if they or their assigns grind their corn in any other place, or refuse to pay him a full and reasonable toll, they are bound to the lord of Gower in a hundred shillings, and to the steward of Gower in forty shillings, and to the said John and his heirs in a hundred shillings.”[4] Iweyn made it nigh-impossible for these people to grind their corn at any other mill by imposing such a steep fee—one hundred shillings (£5) in 1314 is the equivalent of over £4,000 today, and even by today’s standards is a lot for a singular fine. This example of his iron grip on the land might help to explain why Iweyn was targeted and killed directly in association with Despenser during the Marcher lords’ rebellion.

Networks forged through the Hereford Cathedral Muniments are quite detailed on the circumstances of John Iweyn’s death – at least as it pertains to landholding. This means that we have a fairly detailed record of who killed Iweyn, for what land, and what happened to the land after. By mapping his allies, enemies, and those beholden to him, we start to see the shape of the war he was part of, even just through the lens of who seized what land and when.

Land and Connections at Dewsall

Much of Iweyn’s early documentation is in the form of grants of land or license to build. Up to 1311, when he was granted stewardship of Gower, Iweyn had plots of land in the village of Doweswalle (which is modern-day Dewsall) which he tended to and traded around. Iweyn did not sell off this land upon grant of his position in Gower, but from April 1314 onward, all of his land documents have to do with his water mill in Swansea near what is today called Killay. The land did not go to waste, however, as it appears that as of Document 1527 (September 19 1326), Alice recovered Iweyn’s land in Dewsall.

| Recurring Witnesses | HCM |

|---|---|

| Nicholas Iweyn | 468, 678, 684, 683, 682 |

| William de la Calewe | 676, 679, 683, 682, 1053 |

| Nicholas de la Hulle | 676, 679, 683 |

| Simon de Lodelawe | 468, 684, 683, 682, 1053 |

| Edmund le Waleys | 679, 684, 683, 682, 1053 |

| John son of Roger Iweyn | 676, 683 |

| John Vyncent | 679, 683, 682 |

| Thomas de la Barre | 679, 683, 682 |

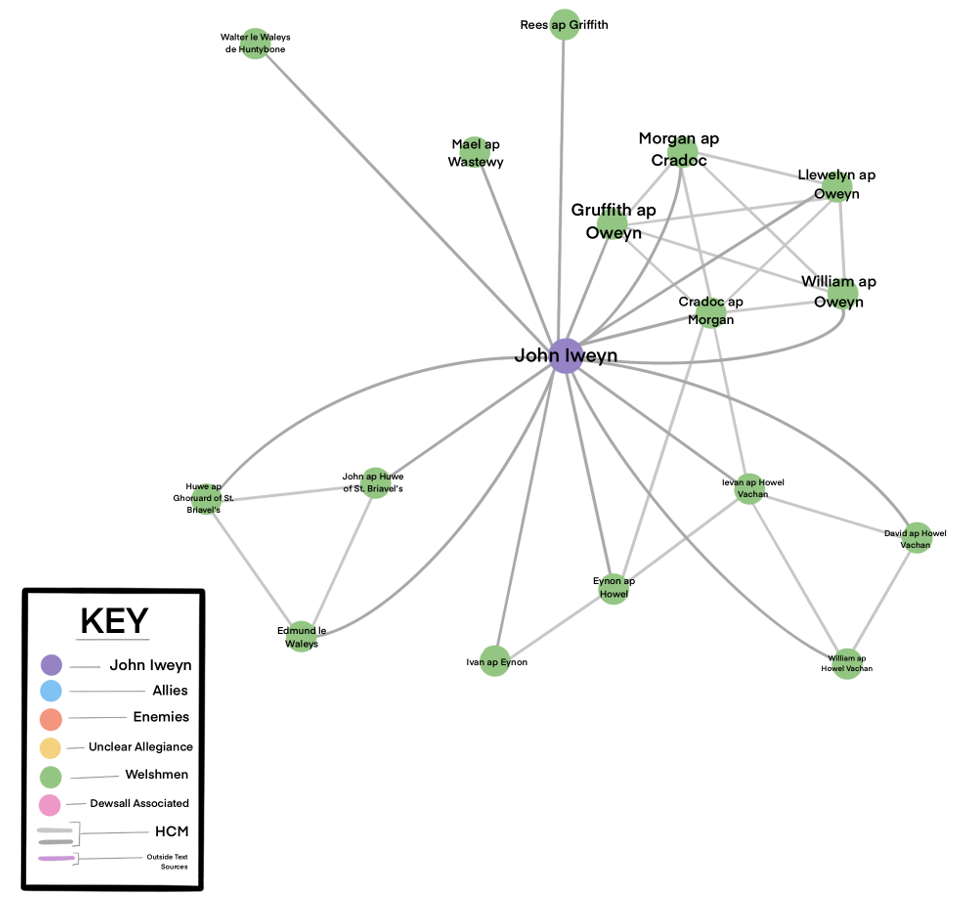

So what are Iweyn’s connections in Dewsall? Figure 3 shows the fellow principles of his Dewsall land documents, and Figure 4 lists recurring witnesses in these cases. The principles listed were, of course, landholders who then sold the holdings to Iweyn. Furthermore, there are at least two other Iweyns mentioned in the muniments, a Nicholas and a Dionisia, and it’s not clear if they’re related to John Iweyn. In fact, we have records of another John Iweyn to whom they might be related instead, or perhaps alongside. The Hereford muniments indicate a distinct John Iweyn, son of Roger Iweyn. In Document 679, the two are named together, John Iweyn as a principal and John son of Roger as a witness, and again in Documents 683 and 1722. It’s possible that in documents where they do not both appear, John son of Roger is referred to only as John Iweyn. There’s no evidence of the relation in the documents we have.

Despite devoting his attention to his stewardship of Gower, John Iweyn still held land and standing at Hereford and in Dewsall, and passed it down to his next-of-kin when he died. The Despenser war didn’t touch these lands, so they remained in his line.

Conclusion

John Iweyn was still incredibly well-connected before his rise to stewardship of Gower, but this rise brought on new opportunities and connections—connections that would lead to his death. Even before he worked under Hugh Despenser the Younger, Iweyn facilitated William de Breose’s heavy-handed rule in Gower and movement with his water mill and those bound or granted to it show this. Ultimately it was his appointment to stewardship and deputization that would lead to his death, but his connections to de Breose and Despenser didn’t help, either.

Through a network lens, we see a man who held a lot of land, and that land passed through hands like changing money. Iweyn’s connections through the lands he held and stewarded led to both powerful people and common folk, but either way, he seemed to be just as ambitious as Despenser in his land-grabbing, if not as powerful.

[1] Charles, B. G., and H. D. Emanuel. A Calendar of the Earlier Hereford Cathedral Muniments. Document No. 1523.

[2] Phillips, Seymour. Edward II.

[3] Charles, B. G., and H. D. Emanuel. A Calendar of the Earlier Hereford Cathedral Muniments. Document No. 1769.

[4] Document No. 1523