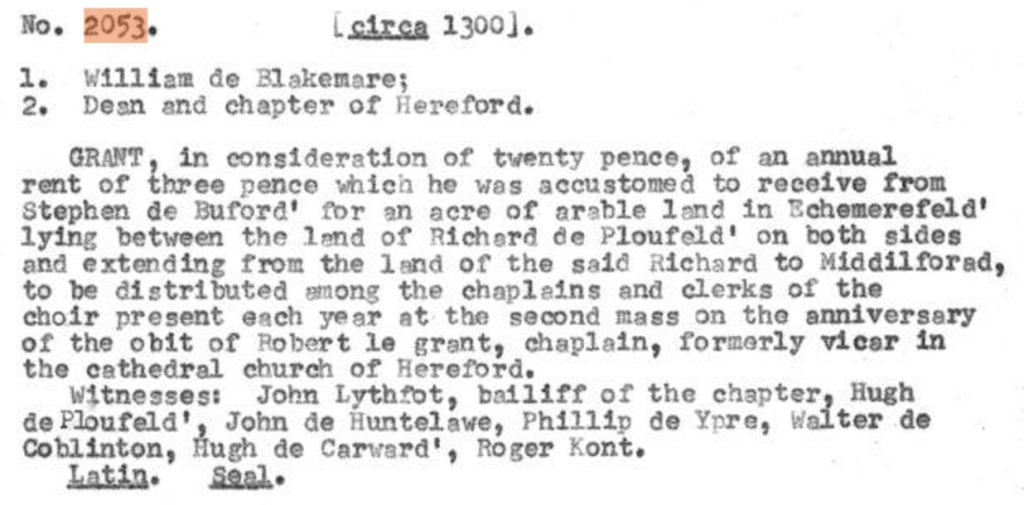

The above document, numbered 2053, is a summary of one of several thousand of the Hereford Cathedral Muniments (HCM), or documents relating to the operation of the cathedral and city of Hereford. HCM documents are one of the major sources of information about life in medieval Hereford. Like the above document, the HCM sources generally function as records or receipts for court or other legal transactions. HCM 2053 describes a monetary transaction between the Dean and Chapter of Hereford and citizen William de Blakemare, and is thought to have been written around the year 1300. William paid the Dean and Chapter, who was the head of the church in Hereford – not to be confused with the Bishop of Hereford – 20 pence, as he had recently gained possession of a grant of land from Richard de Ploufeld, who had paid the Dean and Chapter three pence per year for the land. The document was witnessed by several citizens, including Hugh de Ploufeld, likely a relative of Richard’s, and John Lythfot, noted to be the bailiff of the chapter.

John, whose last name has been normalized in this project’s data to Lyghtfot, appears in 56 Hereford Cathedral Muniments, as well as six other documents collected in this study. In twelve of these, he is explicitly noted to be a bailiff. In seven, he is a clerk, in four, he is dead, and in one, he is seneschal (likely another term for bailiff). Given an occupation in only 24 out of 62 documents, Lyghtfot held the office of bailiff for much of his life – at least 21 years – and likely was functioning as bailiff in documents in which he is not explicitly given that title.

What is a “Bailiff”?

A bailiff in medieval Hereford held a similar position to bailiffs today. In charge of keeping the peace and ensuring order in the courtroom, a bailiff was involved in the regular activities of the courts. Due to the nature of the documents preserved as part of the HCM, which tend to be records of official transactions, ordinances, and more, references to bailiffs appear in these documents often. Generally, bailiffs appear first on the list of witnesses on a given document. The ordering of these witnesses, with bailiffs first, citizens second, and clerks or scribes last, suggests that the bailiffs generally occupied a position of respect and influence within the courtroom. When more important individuals appear as witnesses, they tend to appear at the beginning of the list, with the ordering of witnesses in a document indicating the influence or importance of that particular individual. Magisters and domini, when present, were listed before all others, reflecting their positions of influence. In documents with bailiffs, their positions before other citizens note the bailiffs’ status.

Though the HCM does not contain a record of every document relating to medieval Hereford – 700 years of wear, tear, and political upheaval necessarily have resulted in losses – the prevalence of bailiffs in the surviving documents indicates that many citizens held this position. A total of 67 individual people were named in at least one document as a bailiff of Hereford between 1295 and 1365, with a few other bailiffs named for nearby towns such as Ledbury or Gloucester. This constitutes a small part of the population – with 3801 individuals in the documents, bailiffs comprise less than one percent – but an important one. Some bailiffs, such as Lyghtfot, owned property (Lyghtfot, according to HCM 45, held “a messuage with houses and buildings”) and otherwise exerted influence within the community.

Types of Bailiffs

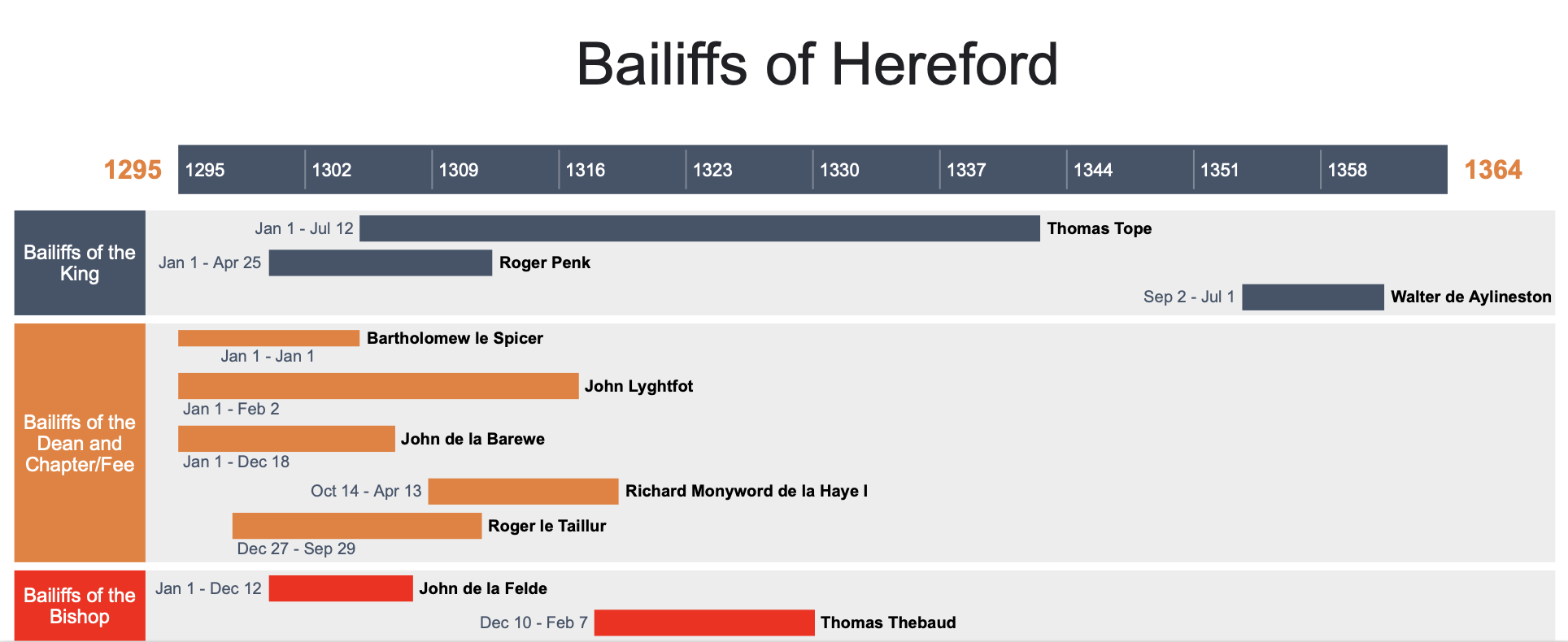

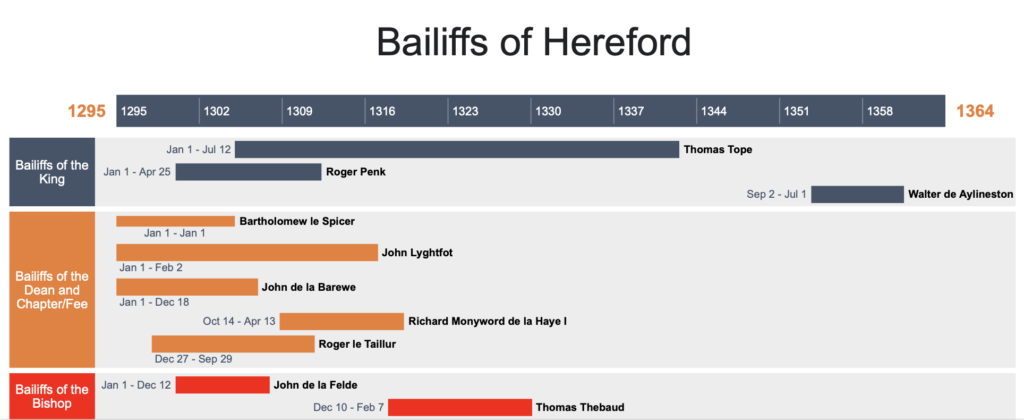

Hereford appears to have had three types of bailiffs active at any given time. These were bailiffs of the king, bailiffs of the dean and chapter, and bailiffs of the bishop. Because of the prominence of Hereford in the early 14th century, the three different types of bailiff served different individuals within the city context. Bailiffs of the king were individuals involved in secular transactions – transactions they witnessed generally involved no clergy, or clergy acting in their capacity as private citizens. For example, Henry de Orleton, bailiff of the king in Hereford from 1311-1312, witnessed a land sale involving his brother Adam (later bishop of Hereford) on Feb. 14, 1311/2, documented in HCM 773. This transaction is typical of bailiffs of the king, who often appear in land sales, monetary settlements, and other such documents unrelated to the operations of the church. Bailiffs of the Dean and Chapter of Hereford were under the authority of the leadership of the diocese, and were involved in transactions relating to the church. John Lyghtfot, bailiff of the Dean and Chapter from the late 13th century until his death in August 1316, witnessed a rental agreement early in his career involving a meadow belonging to the dean and chapter, as shown in HCM 2053 above. Finally, bailiffs of the bishop worked directly for the bishop of Hereford, a highly important individual in the 14th-century church. However, exactly what the duties of the bailiff of the bishop were and how they differed from bailiffs of the king remain unclear – John de la Felde, bailiff of the bishop from 1300-1307, appears as a witness in two documents describing secular land transactions (HCM 375 and 608); why an agent of the bishop was present is not stated.

While I have identified three types of bailiffs, a wide variety of different types of bailiffs appear in individual documents, though many of these appear to refer to the same job. For example, Roger Penk was named on Jan. 8, 1312 as a bailiff of the king in Hereford, on Feb. 14, 1312 as a “bailiff of the town of Hereford” in HCM 773, and again as“bailiff of the king in Hereford” on April 25, 1312, in HCM 207. Clearly, the bailiff of the king must be the same position as the bailiff of the town. John de la Barewe was named as the bailiff of the Dean and Chapter of Hereford in documents dated “circa 1300,” “early 14th century,” March 29, 1306, May 15, 1306, and Dec. 18, 1306, but as the bailiff of the fee in another document dated to the early 14th century. Richard Ingan, Richard Monyword de la Haye I, and Robert le Taillur are all bailiffs of the Dean and Chapter and bailiffs of the fee at various points in their lives. This lends itself to the conclusion that the bailiffs of the Dean and Chapter were also bailiffs of the fee (fee referring to a plot of land, not a monetary payment, in the medieval era). As stated above, however, while the different types of bailiffs may have answered to different people, what exactly differed in their duties is unclear.

Of the 67 bailiffs of Hereford, 9 were bailiffs of the bishop, 14 were bailiffs of the dean and chapter or the fee, and the remaining 44 were bailiffs of the king. The reason for this difference in numbers is twofold: the position of bailiff of the king was typically held by three men at once (as in HCM 93 and 195, both of which name John Monyword, John Ochelmon, and Walter Tope as bailiffs of the king). Two men held the office of bailiff of the Dean and Chapter in Hereford (for much of the first decade of the 1300s, these two men were John Lyghtfot and Bartholomew le Spicer), and one held the office of bailiff of the bishop (Thomas Thebaud alone served from 1317-1330). The above timeline shows four men holding the office of the bailiff of the Dean and Chapter at once – because the Dean and Chapter held lands across Herefordshire, he required bailiffs not only within the city but at his various manors.

Additionally, the office of bailiff of the king appears to have a set term limit, with the majority of these bailiffs appearing in only one document, or in a series of documents within the span of a single year. This implies that while bailiffs reporting to the church may have held the office for many years, the bailiffs of the king held a single-year term.

Lyghtfot: Rank and Influence

Bailiffs who served for many years, such as John Lyghtfot, tended to become well-connected and influential in the community. Lyghtfot owned multiple properties, including the messuage from HCM 45, a home later owned by Hugh de Monniton in HCM 2887, and his wife Margery’s home on the High Street in HCM 77. He came into direct contact with a large number of people, and worked directly for the Dean of Hereford, one of the highest offices within the church. He had two wives during his lifetime, having married Margery sometime around 1280 (CP 25/1/81/19, number 51 on Feet of Fines records their having received a gift of land in 1282) and living with her until she began to live alone shortly before 1300 (recorded in HCM 77, a document which also lists Lyghtfot as a citizen, ie. not yet a bailiff), and having married Alice sometime before his death in 1316 (Alice released land formerly belonging to John in HCM 90). He had no children. Many other families retained the bailiff job amongst themselves, such as the le Werrour family. Philip le Werrour repeatedly served as bailiff of the king, with at least three terms, in the early 14th century, 1311-1312, and 1322. Later, his son Nicholas le Werrour served in the same position in 1337. William and Richard Stevenes (possibly brothers) served as bailiffs of the king in 1356 and 1360, respectively.

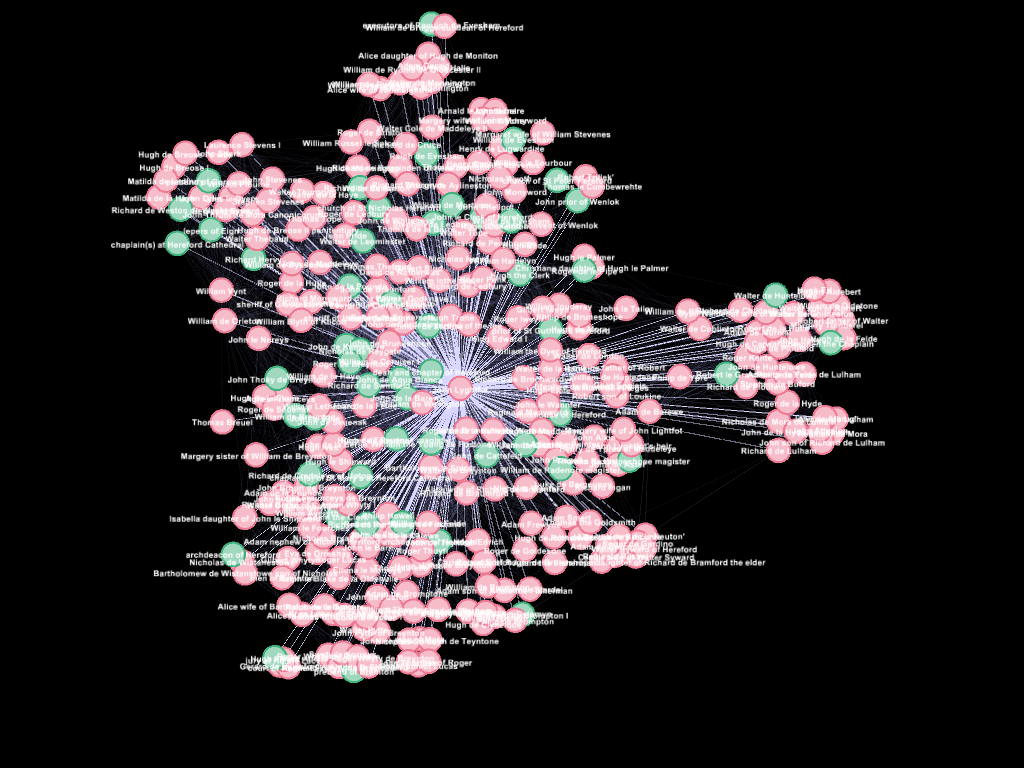

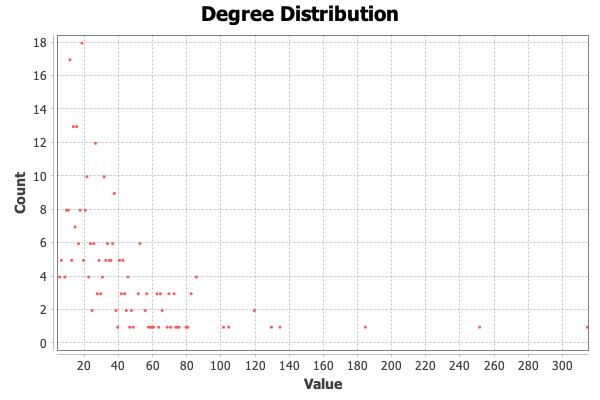

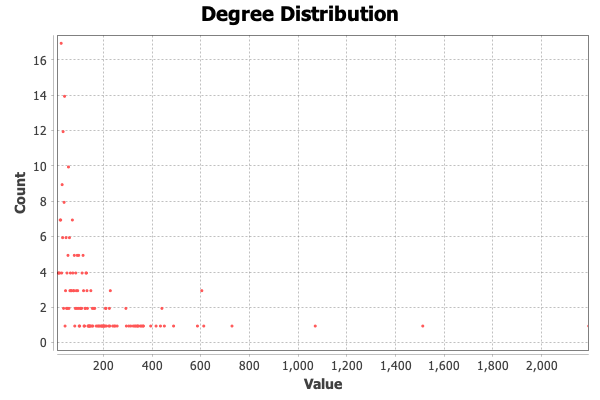

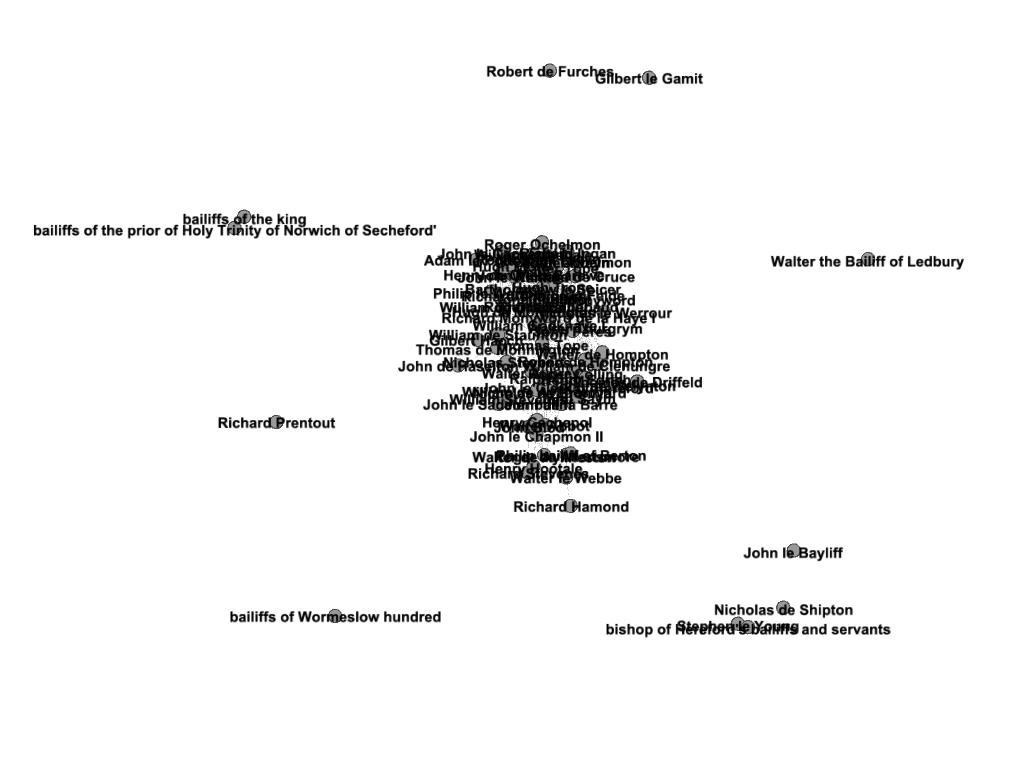

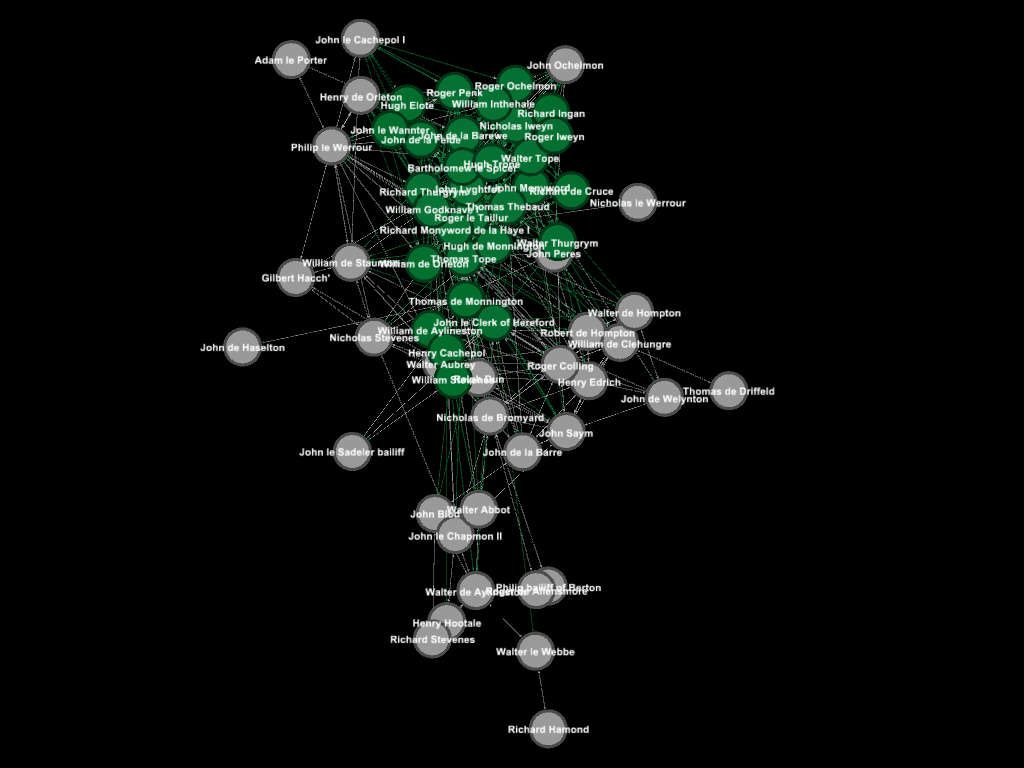

John Lyghtfot, both childless and brotherless, remained a bailiff of the Dean and Chapter until his death. Through this position, he became a well-connected and influential individual over the course of his life. As his ego network, or network of people who appear in documents alongside him, shows, Lyghtfot interacted with a large number of people over his lifetime. Examining the degree and weighted degree of the network reveals just how well-connected Lyghtfot was. Degree is a measurement of centrality – the degree of a node in a network represents how many edges connect to that node. The weighted degree emphasizes how many individual connections emerge from a single node. Weighted degree takes into account people who appear together in multiple documents (adding weight to the edge between the two nodes), while degree does not. The average degree of this network is 33, meaning that each person in the network has connections to 33 other people. Lyghtfot himself has a degree of 320, while most other nodes have degrees between 1 and 60. (Degree is visualized in the first of two “Degree Distribution” graphs below.) The average weighted degree of Lyghtfot’s network, however, is 121. Again, Lyghtfot himself has a much higher weighted degree – nearly 2200 – while most other nodes have below 200. However, even the scale difference between these two visualizations shows that people within Lyghtfot’s ego network tended to appear in multiple documents together, often in documents involving Lyghtfot himself.

Bailiffs who appear in fewer documents than Lyghtfot will of course have a lower degree and will not appear as centrally within the network of early 14th-century Hereford. While bailiffs held significant influence as a representative of either the state or the church, only individuals who were able to hold the office for long periods of time, such as John Lyghtfot, could truly reap the monetary and social benefits. The majority of their job seems to have consisted of witnessing court proceedings, which have come down to us in the 21st century in the form of receipts for land sales, fines paid, and more. While the complete social picture of late medieval Hereford cannot be uncovered from these documents, they can begin to shed some light on an important office within the community.